Key Takeaways

- Despite overwhelming evidence that they drain funds from public schools, harm student achievement, and lack any oversight or accountability, universal voucher laws are proliferating.

- Marketed as a way to lift low-income students out of struggling schools, vouchers are siphoning funds from public schools to primarily benefit wealthier families whose children are already enrolled in private schools.

- Rural schools stand to lose the most state funding as voucher programs are implemented. Eventually many of these schools may be forced to close, severely hurting the communities relying on them.

“None of this makes any sense,” says middle school teacher Liz McDonald. “I have no idea what they think our schools will gain. We will lose so much.”

McDonald teaches in Cache, a small town in the southwestern part of Oklahoma. Cache is roughly 120 miles from Oklahoma City and 200 miles from Tulsa—where the vast majority of private schools in Oklahoma are clustered.

“People talk about ‘school choice.’ We don’t have that choice because private schools are too far away,” McDonald says.

For families in Cache, that usually isn’t much of a concern. “Our schools are supported and valued,” she adds. “They are the heart of this community and so many other rural communities across the state.”

But McDonald is worried. In May 2023, Oklahoma became the latest state to enact a universal or near universal school voucher law that educators and many parents fear will starve public schools, particularly those in rural areas, of critical funding. In Oklahoma, more than half of all public schools serve rural communities.

“We have enough challenges already. We desperately need more resources for students, more counselors, more support staff,” McDonald explains. "With vouchers, they are taking money from our students and giving it to private schools.”

For years, Oklahoma educators and their allies sounded the alarm on vouchers’ staggering record of failure in states such as Florida and (especially) Arizona, as they successfully turned back legislative efforts to bring vouchers to their state. But in 2023, governor and privatization champion Kevin Stitt managed to corral enough support for a scaled back and remodeled version called the Parental Choice Tax Credit Act. When Stitt began to push for expansion and the lifting of spending caps, public education advocates were not surprised.

“What we are seeing and hearing in Oklahoma is exactly what we said would happen if vouchers came here,” says Erika Wright, founder and leader of the Oklahoma Rural Schools Coalition. “This voucher law will grow, and it is going to put us in a situation where we don't have enough revenue to cover basic services across the board, not just public education. ... Ten years from now, we could look like Arizona.”

Arizona’s ‘Billion-Dollar Boondoggle’

So, what is happening in Arizona? Simply put, chaos. The state passed a voucher law in 2012 and a decade later—against the will of the voters—expanded it to become the first universal voucher program in the country. Any family in the state, regardless of income, was now eligible for up to $8,000 of taxpayer funds a year.

The program soon became a runaway train, barreling ahead with zero accountability (leading to widespread fraud and waste), and blowing holes through the state budget, while delivering no academic benefits to Arizona students.

Arizona’s voucher scheme takes shape in the form of an Education Savings Account (ESA), in which a portion of the state funding per student is put into an account that parents can tap into to pay for approved education expenses, including, but not limited to, private school tuition. The annual cost of the program will soon balloon to $1 billion (a “billion-dollar boondoggle,” says Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs), wreaking havoc on the state budget.

“If other states want to follow Arizona—well, be prepared to cut everything that's in the state budget," Arizona Education Association President Marisol Garcia told NEA Today in 2024. “Not just public education but health care, housing, safe water, transportation. All of it.”

Unfortunately, many states have followed Arizona. Eighteen states now have universal vouchers. Another 15 states have limited laws.

The 17 states that haven’t joined these ranks may soon have vouchers, whether they like it or not. The Trump administration is pushing a massive federal voucher plan worth $20 billion over four years as part of its budget reconciliation package. In May, the reconciliation bill narrowly passed the House of Representatives, 215-214, and is now in the U.S. Senate.

Vouchers' dismal record should have blunted any momentum years ago, says Josh Cowen, professor of education policy at Michigan State University. But then again, privatization, not improved student outcomes, is the goal.

“On any standard of professional evidence that researchers have, you really couldn’t find a more comprehensive failure than vouchers,” Cowen says. “Equally ambitious policy schemes have gone the way of the dinosaur for far less worse results.”

The Pressure on Rural Communities

According to the National Rural Education Association, rural schools serve almost 10 million students, and nearly half are from low-income families.

Although the impact of vouchers is being felt in schools and neighborhoods across the nation, it is rural students, their families and their communities who will withstand the worst of this assault on public schools.

Due to significantly smaller populations, rural communities raise less in local taxes, leaving their schools much more dependent on state funding. Vouchers will only worsen an already perilous situation. Any further decrease in these funds—a certainty under vouchers—can quickly lead to cutting things like sports, art classes, and after-school programs.

“When programs are eliminated, families look to other schools and students leave,” says Phil Downs, a professor at Trine University in Angola, Indiana. Even modest declines in student enrollment will lead to more funding cuts.

Eventually, many rural public schools may be forced to close, severely hurting the communities relying on them—a trend already being felt in several voucher states, including West Virginia and Arizona.

“In Indiana, we’re hearing more calls for district consolidation,” says Downs. A former teacher, principal, and school superintendent, Downs has been tracking the financial impact of the state’s 14-year-old voucher law, which became universal in 2024.

Downs’ analysis reveals how districts such as Indianapolis and South Bend, with an abundance of private schools, have seen a major influx of funding while smaller rural districts have incurred a net loss.

Facing this budget crunch, many of these small districts look to local levies and bonds to pay for programs, a steep hill to climb. “It’s a lot of pressure on rural communities,” says Downs. “Because it means a larger tax burden on residents. In Indiana, some succeed, but most fail. And soon, these small schools find themselves in a downward spiral that they can’t escape.”

A Handout to Wealthy Families

Marketed to lift historically marginalized students out of struggling schools, voucher laws in their first stages usually restrict eligibility to lower income families. In later legislative sessions, the program is expanded and eventually becomes universal so that practically any family regardless of income becomes eligible to tap into taxpayer funds.

What happened next? Expenses skyrocket, fraud increases, and families who already have their children enrolled in private schools come knocking. Soon, a program designed ostensibly to help low-income families morphs into a bloated subsidy for wealthy families.

Quote byBrookings, “Arizona’s Universal Education Savings Account Program Has Become a Handout to the Wealthy,” May 2024

According to an analysis by Brookings, families in the wealthiest communities in Arizona are obtaining ESA voucher funds at the highest rates, while families in the poorest communities are the least likely to obtain these funds. More than 75 percent of vouchers go to students who were already enrolled in private school.

Recent data released by the Oklahoma Tax Commission revealed that of the $191 million paid out in tax credits for private school tuition in 2024, 30 percent went to families making between $75,000 and $150,000 and 17 percent went to families making between $150,00 and $225,000. Roughly 20 percent went to families making over $225,000. The median household income in Oklahoma is roughly $60,000.

“Why are we giving free money to people making over $200,000?” asks Liz McDonald.

The same question is being asked in practically every state with universal vouchers.

Eligibility is Not Access

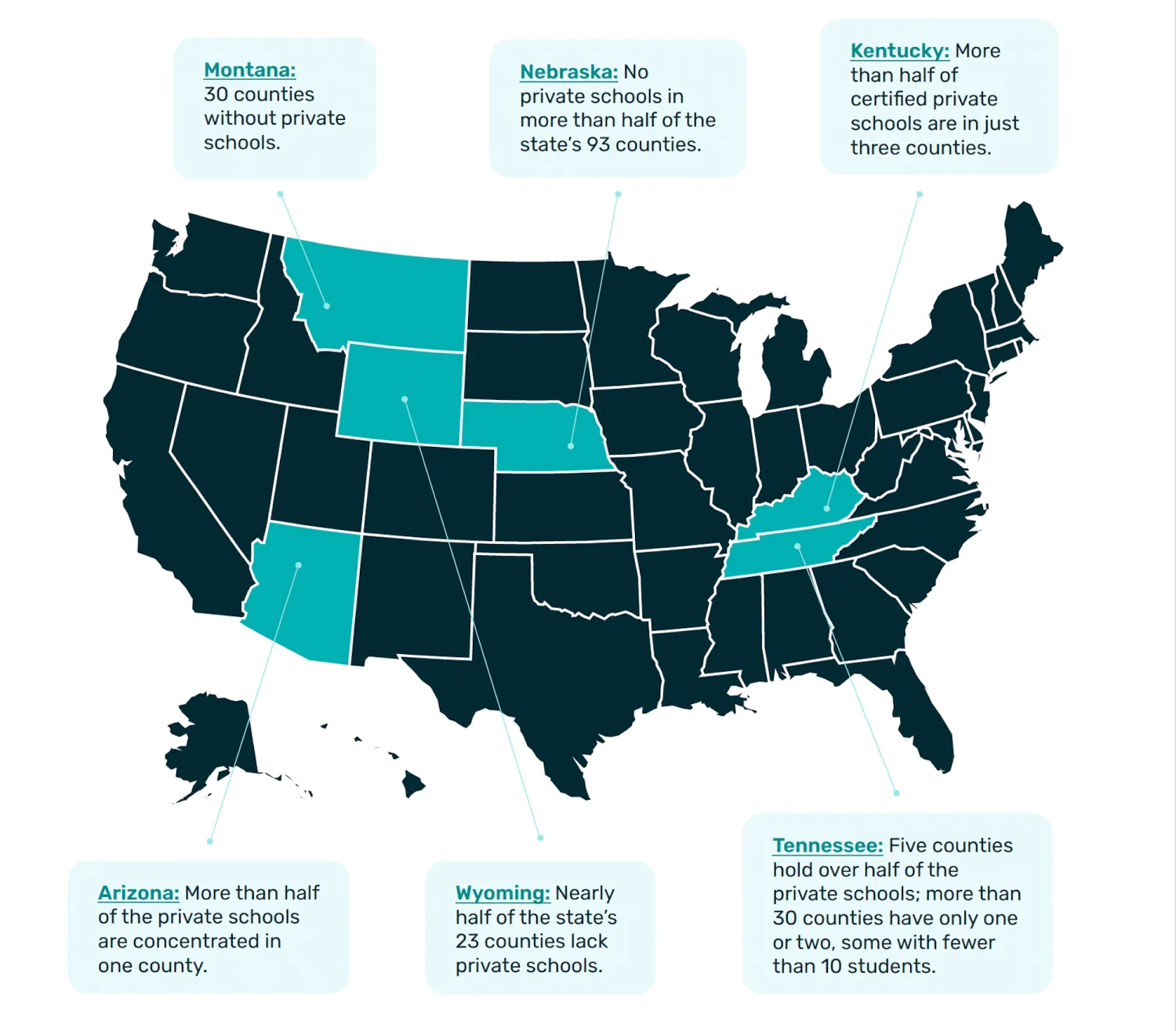

Private schools that do exist in, or somewhere near, rural areas are often few and far between. Students face long distances to attend them—often an insurmountable obstacle for many families. Many private schools do not provide transportation for students.

In Wishek, North Dakota (pop. 841), where Lisa Hendrickson teaches upper elementary, families would have to travel up to 120 miles round trip to send their kids to the closest private school. “It’s nearly geographically impossible for these families to access private schools,” Hendrickson says.

And if they were somehow able to travel these distances, could their families really afford these schools? What kind of education would they receive? And would they even be admitted? Unlike public schools, private schools can refuse to accept children because of their disability, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and more.

As voucher programs became universal, new private schools proliferated. But many of them were inferior and closed, says Cowen.

“Families are led to believe that there are a whole lot of high-quality private school providers that will take all of these children in mass amounts,” he explains. “We know that doesn't happen. We know the schools that do accept them tend to be barely hanging on, tend to be ‘subprime’ as I call them, as the academic results show.”

Wright says if a lower income family in Oklahoma wanted to access one of the top-performing private schools, voucher funds worth $7,000 wouldn't come close to covering tuition. “These schools cost up to $25,000 a year. How are these families going to pay the rest? That's like giving me a voucher to shop at Neiman Marcus. 'Oh great—thanks for paying for my parking!’”

Furthermore, voucher expansion tends to be followed quickly by sharp increases in private school tuition. According to a 2024 Princeton University study, after Iowa’s voucher program became universal, private schools increased prices on average by 25 percent. One year into Oklahoma’s voucher law, approximately 20 percent of private schools raised tuition anywhere from 6 percent to 100 percent, obviously far past the inflation rate.

‘What Will Our Schools Look Like?’

In the 2025 legislative session, North Dakota United helped beat back a slew of voucher bills, leaving educators who mobilized against the privatization push triumphant, but also a little exhausted.

“I’m hoping they got the message and will now go away,” says Lisa Hendrickson. “But we know better.”

Voucher proponents are nothing if not relentless—and will even go to great lengths to avoid having the issue brought before the voters—fully aware that when it is on the ballot, vouchers lose. “The public knows vouchers harm students and does not want them in any form,” says NEA President Becky Pringle.

Wright agrees. “Vouchers are not popular in Oklahoma—with anyone. I’m a registered Republican and I’ve spent hours knocking on doors and talking to Republican families. They do not support vouchers. But when it comes to electing our leaders and lawmakers, larger national narratives override their concerns about what is happening to our public schools.”

In 2024, educators in Nebraska led a successful effort to put the state’s voucher law on the November ballot, giving voters the opportunity to vote on the issue, up or down. Voucher proponents appealed to the state Supreme Court to remove the referendum but were overruled. On Election Day, Nebraska voted overwhelmingly to repeal the law. Colorado and Kentucky voters also delivered a similar rebuke to vouchers.

“If it came down to a public vote for the public to vote on, I would be willing to lay all my money on the common sense of North Dakotans,” says Hendrickson. Although her state is still voucher-free, Hendrickson knows privatization lawmakers and advocates will be back in the next legislative session.

“The message about vouchers shouldn’t just come from union members, educators, and others in the school system,” Hendrickson says. “Legislators have to hear from the general public, our neighbors, people in the community. Vouchers only benefit the select few and that means less money for our schools and students. People need to ask themselves: If vouchers pass, what will our schools look like down the road 5 or 10 years from now? How are we going to manage that financial loss?”