Key Takeaways

- Classroom censorship laws, like the one in Georgia and many other states, mean teachers live in fear of crossing an “invisible line” in their classrooms.

- As a result, many educators are removing books from their libraries, not engaging in classroom discussion with students—or simply walking away from the profession they love.

- But the fight is on. Just last week, the Tennessee Education Association filed suit, challenging the constitutionality of that state’s classroom censorship law. And many educators and community members are involved in read-alouds and other protests.

[Editor's note: On August 17, the Cobb County school board voted 4-3, along party lines, to fire Rinderle, despite the recent recommendation of a district-appointed tribunal to keep Rinderle in her job. In a statement, released after their vote, Rinderle said: "The district is sending a harmful message that not all students are worthy of affirmation in being their unapologetic and authentic selves. This decision, based on intentionally vague policies, will result in more teachers self-censoring in fear of not knowing where the invisible line will be drawn."]

Nearly six months ago, on the day before Valentine’s Day, Due West Elementary School in Marietta, Georgia, held its annual Scholastic Book Fair. Hundreds of picture books, early reader books, and more were available for purchase by students, parents, and Due West educators.

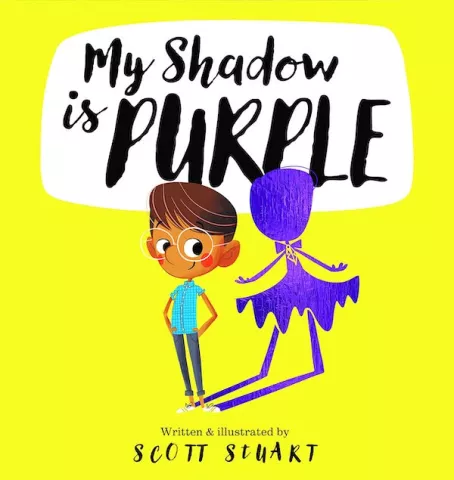

Due West’s gifted specialist Katie Rinderle spent $30.96 on four picture books, including Doña Esmeralda Who Ate Everything by Melissa De La Cruz, about a stylish old lady who lives on diet soda and the uneaten food on children’s plates, and My Shadow is Purple by Australian author Scott Stuart.

My Shadow is Purple sat on her shelf for a month, until Rinderle’s fifth graders chose it for their morning read-aloud. The next day, following a parent complaint, Rinderle was called into the principal’s office. The book was “divisive,” she was told. The following week, she was sent home for good—and, on June 6, she was issued a formal letter of termination, which she is appealing with help from her union, the Georgia Association of Educators (GAE), and the Goodmark Law Firm.

Today, Rinderle is believed to be the first teacher in Georgia to have been fired because of a trio of vaguely worded 2022 state laws that ban teachers from teaching “divisive concepts.”

Educators fear she won’t be the last, which is likely the point of the Georgia legislation and similar classroom censorship laws in other states. “Teachers are fearful of [crossing] the invisible line in their classrooms… because they don’t know where it is,” says Rinderle. So, they self-censor, pulling books from their shelves and shutting down student discussions. Or they just quit.

The consequence is a grim and limited education for students, who are experiencing less access to dedicated teachers, diverse books, and honest and accurate history lessons.

But NEA members—through their unions—also are fighting back.

Classroom Censorship Laws On the Rise

Georgia isn’t the only state censoring, even firing, teachers. Since 2021, 18 states have passed laws that restrict teaching about racism and sexism, according to Education Week, and 15 have laws restricting or banning discussion of LGBTQ+ people or issues, according to the Movement Advancement Project.

Most of the bills center on a list of “divisive concepts” rooted in a 2020 executive order from former President Donald Trump. That order, which was revoked by President Biden, banned federal agencies from certain types of diversity trainings, including those that talked about people’s unconscious biases or the nation’s long history of racism and racist violence.

In Florida, the “Don’t Say Gay” and “Stop W.O.K.E. Act” laws mean teachers have draped their classroom libraries in sheets and been forced to remove books including The Bluest Eye by Pulitzer Prize-winner Toni Morrison, The Diary of Anne Frank, as well as biographies of baseball player Roberto Clemente, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayer, and others.

As a result, many Florida teachers are resigning. “I’m not the first to leave and I won’t be the last—support us, trust us, protect us, or lose us,” warned Hernando County teacher Daniel Scott. Weeks earlier, Scott’s colleague—who also quit—told school board members: “Nobody is teaching your kids to be gay. Sometimes they just are gay.”

One Florida teacher resigned after staff removed bulletin-board posters of Black leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Harriet Tubman. Another resigned after a State Department of Education investigation was launched into her showing students a Disney movie with a gay character. And, of course, there’s the one forced to resign after showing students an image of Michelango’s David.

In January 2023, Florida had 5,294 unfilled teaching jobs, according to the Florida Education Association. In 2019, that same number was 2,219. It’s the worst teacher shortage in Florida’s history, affecting students daily. Indeed, the Hernando math teacher who resigned pointed out that her math students outscored the county average by 15 percent, “and now a sub will take my spot in my cold, bare classroom.”

And it’s not just Florida either. Last month, in Wisconsin, teacher Melissa Tempel was fired after she criticized her district’s decision to ban her first graders from singing the song “Rainbowland” by Dolly Parton and Miley Cyrus.

And, in South Carolina, high school teacher Mary Wood has run afoul of the school board for planning to use Te-Nehisi Coates’ book Between the World and Me in her Advanced Placement class. Wood’s lesson was banned when two White students complained the book made them feel “guilty for being White.”

The Lesson that Got Rinderle Fired

Rinderle read My Shadow is Purple before buying it. She liked it. “I just thought it had a wonderful message: Be true to yourself, embrace others,” she says. Essentially, the award-winning book is about “finding value in [yourself],” which leads to students developing greater self-confidence and well-being, she says. For gifted students especially, who often feel different and excluded from their peers, it’s heartening to hear a story about valuing and embracing the differences in people, says Rinderle.

On the first page, the Shadow’s rhyming narrator explains how “my dad has a shadow is blue as a berry” while Mum’s is “as pink as a blossoming cherry,” but “mine is quite different. It’s both and it’s none.”

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00And, on a subsequent page: “Why can’t I love sport and dancing and trains? And ponies and glitter and engines and trains? Why must I choose and exclude all the rest? I love choosing both because both is the best.”

Rinderle reads books aloud to her students—from kindergarten through fifth grade—because it’s a proven strategy to help build community in the classroom. First, she reads. Second, she guides them in group discussion. And then, she assigns them a thinking task to complete in their sketchbooks. On this particular day, Rinderle asked them to write their own “shadow poems.”

Their work was just wonderful—and it is driving Kennesaw State University Professor Roberta Gardner a little crazy that none of Rinderle’s critics can see that. “The writing that the kids did was just phenomenal,” says Gardner, an expert in literacy education who teaches aspiring and certified teachers.

An article from the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) quotes some of the poems. Wrote one student: “My shadow is white, an underestimated thing. When mixed with colors, it can do amazing things but left by itself it’s kinda bland.”

“This is reader-response theory in action!” says Gardner. Developed by the late Louise Rosenblatt, the theory posits that every reader takes unique meaning from a text. “Whenever we read anything, there is the reader, there is the text, and there is what Rosenblatt called ‘the poem’ that comes out of that intersection,” explains Gardner. “Authors will tell you that once it’s out of their hands, it becomes whatever it is for the reader!”

It frustrates Gardner that lawmakers are writing these classroom censorship laws—and school boards are enforcing them—without understanding how students learn. “I just wish it was a broader conversation about reading and also certainly about inclusivity,” she says. “What families and what children were considered when [these laws] were written?”

The Fight Is On

National polls show most Americans agree with NEA members that students should be able to read books with characters that look like them. Regardless of political party, parents also say students should learn the truth about American history, including about chattel slavery and the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. A majority also say they’re concerned politicians are banning books based on their personal opinions.

Together, many of these parents are working with NEA members to get diverse books back into the hands of teachers and enable students to learn about what NEA President Becky Pringle calls “the history, beauty, and diversity of their world.”

Just this week, the Tennessee Education Association (TEA) filed a federal lawsuit, challenging the constitutionality of the state’s “prohibited concepts” law, which “interferes with Tennessee teachers’ job to provide a fact-based, well-rounded education to their students,” said TEA President Tanya T. Coats.

Lawsuits also have been filed in Florida, Oklahoma, and New Hampshire. In Florida, in November, a federal judge partially blocked the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” preventing it from taking effect in the state’s public universities. “The First Amendment does not permit the State of Florida to muzzle its university professors, impose its own orthodoxy of viewpoints, and cast us all into the dark,” wrote U.S. District Judge Mark Walker, in his ruling.

Meanwhile, in Georgia, union members and community supporters are standing with Rinderle. In late July, the Zinn Education Project and GAE sponsored read-alouds of My Shadow is Purple in coffee shops, bookstores, churches, and hair salons. On July 29, the Teach for Freedom Collective gathered people in an Atlanta park to read aloud their favorite culturally affirming books.

High school social studies teacher Sally Stanhope helped organize the event. As a civics teacher, she risks violating the “divisive concepts” law daily, she says.

Teaching students to be participating members of democracy means encouraging them to challenge ideas, engage in dialogue, and address the issues of the day. “One of the tenets of the law is that you shall not make any students uncomfortable,” she says, but it’s part of her job to make them academically uncomfortable, to help them take risks and grow—in a safe and welcoming space where she sees them for who they are.

She knows Georgia teachers who are afraid to lose their jobs. But she also knows that, through her union, educators have the power to change things. “I joined GAE last year because they give you a means to speak up and build community,” she said.

What’s Next?

In early August, the Zinn Education Project also is organizing a back-to-school read-aloud for Georgia teachers to read My Shadow is Purple or other frequently challenged books, such as I am Ruby Bridges, which the project will send free to participating educators. “We’re at a point where there needs to be a collective response,” says Zinn co-director Deborah Menkart.

Meanwhile, Rinderle awaits her final hearing in August as well. Her attorney, Craig Goodmark, is confident that she will be returned to the classroom. When she is, Rinderle says she will continue to put her students front and center. “I hope I continue to grow. I hope I continue to get better. My goal is always to place my students at the center of what I teach and how I teach,” she says.

The bigger issue, says Goodmark, is that the law remains. “Anytime anybody wants to take a shot at you, they have the ability to do that, under a law that’s so intentionally vague,” he says. “She’s going back—and she’s going to continue to be a great teacher—but she’s going to have to contend with this.

“It seems like they created this law to create havoc with public school teachers,” he says.

At least the ones who remain.