Key Takeaways

- Voucher expansion is re-segregating schools by race and income and reflects a policy rooted in resistance to school integration.

- Programs framed as equity tools often become subsidies for families with means.

- The new federal voucher program risks scaling these harms nationwide.

In many states across the country, voucher expansion has resegregated schools and intensified economic sorting, concentrating wealthier and disproportionately white students in private settings while leaving public schools with higher-need and lower-income populations.

A ProPublica investigation found that dozens of private schools in North Carolina established during the desegregation era are now receiving millions in public dollars via vouchers. Many of these schools remain overwhelmingly white while operating in counties with large or majority-Black populations, essentially resegregating schools through private enrollment and public dollars.

When the state’s current voucher program launched, in 2014, more than half of recipients were Black students. Today, that number has dropped to roughly 17 percent, as higher-income families, many of whose children were already enrolled in private schools, now make up the majority of new voucher users.

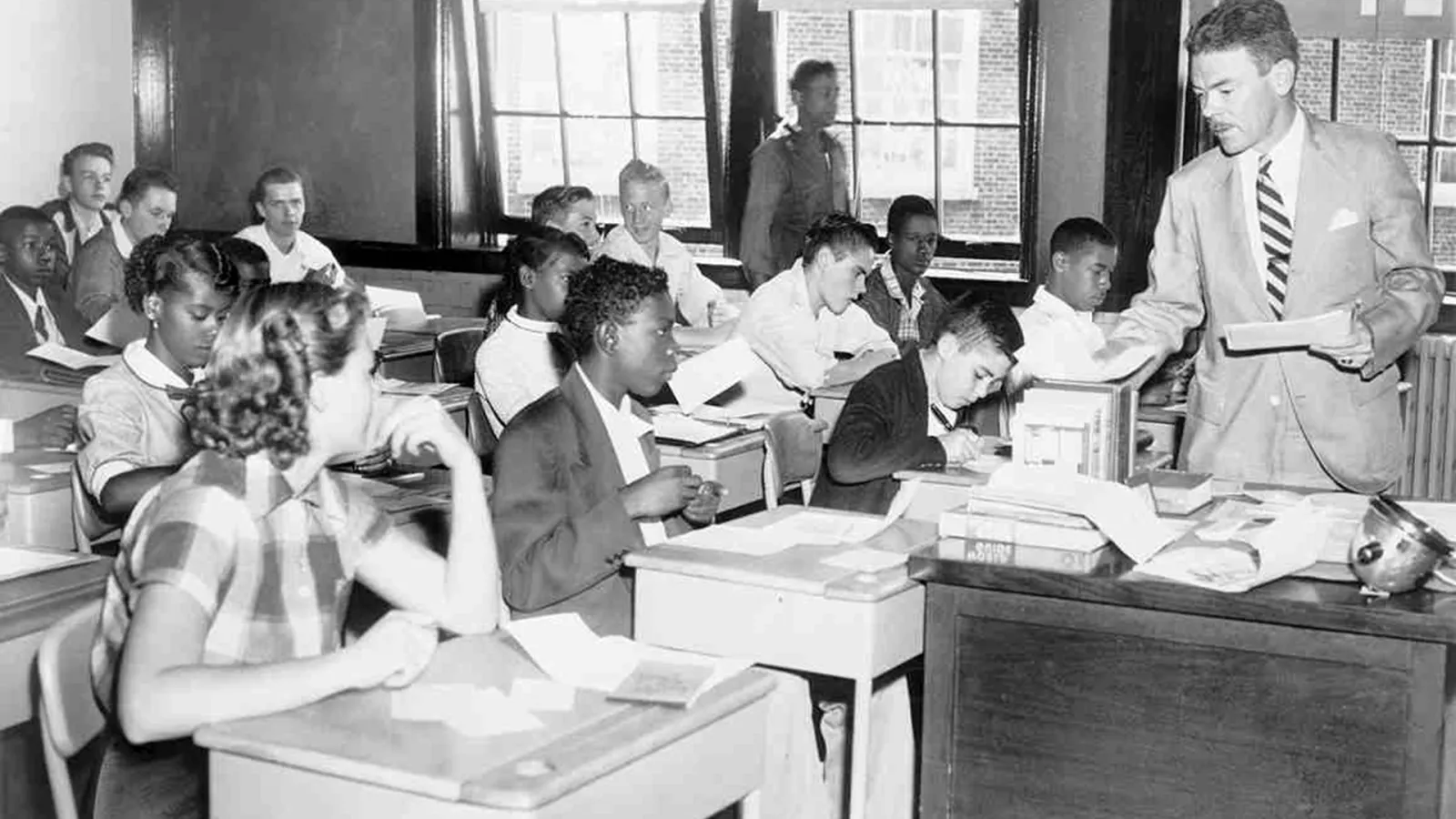

What’s happening in North Carolina reflects trends nationwide. More than 30 states now operate voucher or voucher-style programs, and at least 18 have adopted universal eligibility. This isn’t a new phenomenon. School vouchers were first deployed in the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education as a way to preserve racial separation after courts ordered public schools to integrate.

Born out of resistance to desegregation

Early voucher programs were designed explicitly to undermine school desegregation after the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown.

After the Court ruled segregated public schools unconstitutional, white lawmakers across the South searched for ways to dodge integration. They found a loophole in Brown.

"They realized that Brown v. Board of Education applies to public schools," says Janel George, a law professor at Georgetown University. "They could evade school desegregation by going to private schools."

But private schools cost money. To make them accessible to white families resisting integration, states created tuition grants and “freedom of choice” plans—early versions of vouchers—using public funds.

“These were set up to give white families that wanted to evade school integration public funds to send their children to private schools to maintain a dual segregated system of education,” she says.

Segregation academies and public subsidies

George explains that in southern states hundreds of private schools—later known as segregation academies—sprang up in the late 1950s and 1960s. Many were supported directly or indirectly by public money, including tuition grants, tax credits, donated buildings, and even public school textbooks and teachers.

In Prince Edward County, Virginia, officials went further. Rather than integrate, the county shut down its entire public school system for five years. White students received state-funded vouchers to attend private academies. Black students were left with no formal education at all.

George quotes NAACP civil rights attorney Oliver Hill: “No one in a democratic society has a right to have his private prejudices financed at public expense,” he said of these programs.

Courts eventually struck down many explicitly segregationist voucher schemes. But the underlying idea—that public money could be redirected to private education outside public accountability—survived.

How the past shows up in the present

Modern voucher programs still operate outside the civil rights and accountability structures that govern public schools. Private schools can select students, exclude high-cost populations, and close with little warning. Public schools remain obligated to serve everyone and with fewer resources.

But research shows vouchers often increase economic stratification and discrimination.

In Arizona, for example, where lawmakers made vouchers universal, in 2022, about 70 percent of new voucher users were already in private schools, turning the program into a subsidy for families who could already afford tuition.

“There is no accountability or transparency built into the system,” says Marisol Garcia, president of the Arizona Education Association.

Voucher-funded private schools are also legally permitted to exclude students. An analysis of Tennessee’s new voucher program found that many participating schools maintain policies allowing them to deny admission or expel students based on disability status or LGBTQ+ identity.

Chris Sanders of the Tennessee Equality Project described this as “subsidizing discrimination,” according to the Nashville Banner.

Students with disabilities who use vouchers often unknowingly waive their rights under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. LGBTQ+ students face disciplinary codes that define queer identities as “incompatible with enrollment.”

Protecting public education as a public good

“When you reframe public education as this whole marketplace, it really undermines public education as a public good to prepare students for democratic participation,” says George. “Instead, it focuses on this consumer gain, economic, social, and political advantage.” She adds:

Quote byJanel George, law professor at Georgetown University.

For civil rights advocates, the throughline is clear: “Private school vouchers are being sold to us as choice and freedom,” says Nadine Smith, president and CEO of Color of Change. “But we need to be clear about what they really are. They’re a scheme to defund public schools, to funnel taxpayer dollars to unaccountable private institutions, and leave Black children and working families with fewer resources and fewer opportunities.”

Federal school vouchers deepen divide

Some elected officials have continued to threaten to rip funds from students through school voucher programs to bankroll private schools for the wealthy.

In July 2025, Congress authorized the nation’s first federal private school voucher program. The policy, structured as a federal-tax credit “scholarship,” allows individuals to donate up to $1,700 a year to so-called scholarship granting organizations (SGO)—nonprofits that accept donations—and receive a dollar-for-dollar federal tax credit.

States must opt in, but once they do, families earning up to 300 percent of an area’s median income are eligible to receive private school vouchers funded by those donations.

The program could divert between $30 billion and $50 billion away from public education nationwide, surpassing federal investments in Title I schools and students with disabilities. Unlike public schools, private schools participating in the program are not required to follow the same academic standards, civil rights protections, or accountability measures.

“Congress has potentially committed more funding to school vouchers than it has committed to the two largest pre-K-12 federal public education programs,” says NEA President Becky Pringle.

What to expect from a federal voucher program?

The consequences are already clear from state-level voucher programs: Declining public school budgets, increased segregation, academic harm to students who use vouchers, and taxpayer funding of schools that openly discriminate.

“Vouchers transfer hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to private schools and home schools with little or no academic standards or financial oversight,” Pringle says. “They are designed to undermine public education by siphoning taxpayer dollars meant for public schools and putting that into private hands.”

As states weigh whether to opt into the new federal voucher program, the debate continues to be about whether the county is willing to repeat a familiar pattern: “Using taxpayer dollars to fund discrimination and segregation,” says Linh Dang, NEA senior policy specialist.