Key Takeaways

- Understanding where the term “boycott” comes from leads to an understanding of how collective economic resistance became a powerful democratic tool.

- From the Montgomery bus boycott to the 1960s boycotts in Chicago and New York, young people and families organized strategically to demand equity.

- These movements show how disciplined, collective action can model civic engagement and democratic participation for students today.

Fun fact: The word boycott comes from a person’s last name. In 1880, Charles Boycott, a British land agent in County Mayo, Ireland, became the focal point of an organized campaign by tenant farmers protesting high rents and evictions. Rather than resorting to violence, the community chose a different tactic. They refused to work for him, sell to him, buy from him, or even speak to him.

Crops rotted in the fields. Deliveries stopped. Boycott ultimately required armed protection to harvest his land. These events drew international headlines, and his name entered the English lexicon as a verb.

The strategy itself, however, was older than the term. Decades earlier, American colonists had organized nonimportation agreements to protest British taxation, refusing to buy goods such as tea and textiles in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War. Enslaved people, too, resisted through work slowdowns, sabotage, and other forms of labor withdrawal, recognizing their coerced labor was the engine of the plantation economy.

Long before the term even existed, communities understood that withholding participation could be a powerful form of pressure, which has held true through modern history and today.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

This truth came into sharper focus in the 1950s and 1960s, when civil rights organizers transformed boycotts into disciplined, mass movements—most notably through coordinated economic protests that challenged segregation.

In the winter of 1955, the streets of Montgomery, Ala., bore the weight of weary feet and courageous hearts. Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to surrender her seat to a white passenger lit a match that would ignite the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a protest that became a blueprint for the power of nonviolent direct action.

Led by a then-unknown pastor named Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the African American community of Montgomery walked, organized carpools, and endured harassment for over a year.

Their goal was simple but profound: To end segregation on public buses. Their tools were not bricks, but discipline, patience, and an unwavering commitment to justice. When the Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional in 1956, it was a hard-won victory that spread through the rest of the Civil Rights Movement.

But the movement for equity didn’t end with buses.

Teaching the Bus Boycott

The Zinn Education Project’s Montgomery Bus Boycott lesson invites students to explore the yearlong protest through the voices of those who lived it. Using primary sources, role-play, and critical discussion, students examine how everyday people organized carpools, mass meetings, and community networks to sustain the boycott.

Boycotts for Strong Public Schools

Less than a decade later, in 1963, Chicago saw a different kind of boycott—this time led by students and parents who stood against Superintendent Benjamin Willis and the "Willis Wagons." Instead of integrating Black students into white schools, Willis put Black students into mobile classrooms, apart from white students.

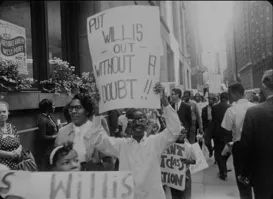

On October 22, 1963, more than 200,000 Chicago students boycotted school as part of “Freedom Day.” Another 10,000 students, parents, and community members protested outside the headquarters of the Chicago Board of Education. Some signs read “Willis Must Go,” or “No Willis Wagons,” while others demanded integrated schools.

A year later, in 1964, New York’s Black and Puerto Rican communities boycotted in response to deeply segregated schools. Led by parents, students, and educators and organized by civil rights groups such as the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality, more than 460,000 students stayed home for a day, making it the largest school boycott in U.S. history.

Though Brown v. Board of Education had outlawed school segregation a decade earlier, Black and Puerto Rican children in New York were still confined to overcrowded, underfunded schools, largely due to discriminatory housing practices and political inertia.

“While the Chicago and New York boycotts were largely met with silence by city politicians at the time and no meaningful policy change followed, they exposed deep fault lines in American democracy,” says Aaron Dorsey, a national trainer with NEA's Center for Racial and Social Justice.

1963 Chicago School Boycott

This Zinn Education Project lesson examines the massive 1963 Chicago school boycott, when more than 200,000 students stayed home to protest segregation and overcrowded conditions in Black schools. Through primary sources and historical context, students explore how families, organizers, and young people pushed back against discriminatory practices.

NEA's Quiet But Bold Stand

Even earlier, in the 1940s, a quieter but no less significant stand was taken by the NEA. At a time when racial segregation was not only accepted but codified into law in many cities, NEA made the bold decision not to hold its annual Representative Assemblies in any city that discriminated against delegates based on race.

This act of institutional boycotting, using an organization’s economic and political weight to resist injustice, sent a message to cities across America: Equity wasn’t negotiable.

NEA's action demonstrated that change could also come from within institutions willing to put principle over convenience.

Why This History Matters Now

Today, educators across the country face increasing pressure from book bans, curriculum restrictions, and politically motivated attacks on teaching an honest history. Voting rights are being chipped away in states across the country. Some politicians decry “wokeness” in schools while ignoring the systemic inequities that persist in education and housing.

“Boycotts and nonviolent direct action are living tools used by people who refuse to accept injustice as normal," says Dorsey. "Whether it's through marches, walkouts, economic boycotts, or school strikes, these tactics force attention, disrupt complacency, and create political pressure where polite appeals fail.”

The movements of today resemble the strategy of the 1960 Greensboro sit-in, when four Black college students sat down at a segregated Woolworth's lunch counter in North Carolina and refused to leave after being denied service. Their act of defiance sparked a wave of of similar sit-ins across the South. Like the Greensboro students, young activists today—organizing walkouts against ICE raids, gun violence, climate inaction, and racial injustice—are the modern manifestations of a long tradition.

“When students organize and protest, they’re not being ‘disruptive,’” explains Dorsey. “They’re participating in the most American form of civic engagement. And when we support them, by teaching the history, guiding the discussion, and defending their rights, we’re not just educators—we’re stewards of democracy.”