Key Takeaways

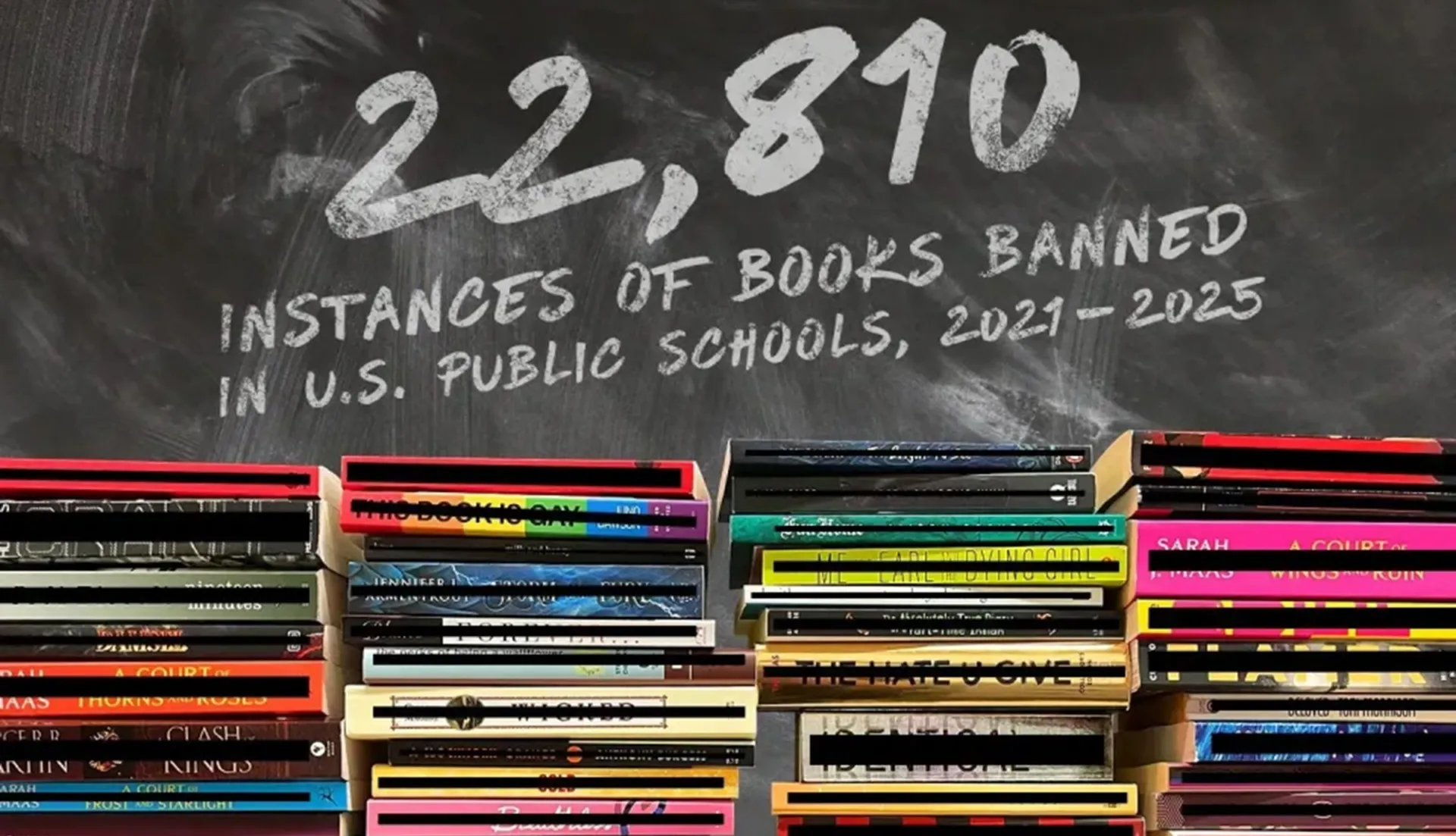

- Since 2021, PEN America has tracked 22,810 cases of book bans across 45 states and 451 school districts—but likely the number of books taken out of students’ hands is even bigger.

- Even as book bans grow common, thanks to a few extremist politicians—and lately, the efforts of the federal government—most Americans oppose them.

- Parents and educators are working together to pass school board resolutions and state laws that protect students' right to read. Authors also are involved!

9 in 10

2 in 10

Book banning has become the new normal in American public schools, a new report from PEN America has found.

“Never before in the life of any living American have so many books been systematically removed from school libraries across the country…Never before has access to so many stories been stolen from so many children,” states the report, called “The Normalization of Book Banning,” which PEN released on October 1.

Meanwhile, the fight to stop bans also is spreading, as educators and parents keep pushing for students’ freedom to read books with LGBTQ+ characters, with Black and brown characters, with Jewish and Muslim characters, and other stories and history that reflects the diversity around us.

“It’s a disservice to the kids, to not learn about the world around them,” says Becky Vevle, a middle school language arts teacher in St. Francis, Minnesota, where the local union filed a lawsuit earlier this year, alleging the district was unlawfully banning books “based on the ideas, characters, and stories they contain.”

Across the nation, educators and parents are standing up at school board meetings, urging boards to pass NEA’s Freedom to Learn resolution. They’re also organizing in local groups to defend books, using tools (like social media graphics, talking points, and more) provided by Unite Against Book Bans, of which NEA is a partner. As their message is heard, public opposition to book bans is growing.

So Many Books, So Many Bans

During the 2024-2025 school year, PEN recorded 6,870 instances of book bans. Since 2021, that’s 22,810 cases of book bans across 45 states and 451 school districts. But likely the number of books taken out of students’ hands is even bigger, as many educators quietly remove books that could cause problems for them.

Florida led the nation in bans with 2,304 bans in 2024 - 2025, PEN found. Texas, at 1,781, and Tennessee, at 1,622, are second and third in the nation in the number of bans.

Key trends among bans this year:

- The federal government’s involvement in book bans is new, PEN notes. In July, the Trump administration removed almost 600 books from Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) schools. In response, a dozen students, ranging in age from pre-K to 11th grade, sued, alleging the book bans violated their First Amendment rights. The books removed included content around slavery, Native American history, LGBTQ+ people and history, as well as parts of the AP Psychology curriculum. One book that was banned: “You Call This Democracy? How to Fix Our Government and Return Power to the People,” by Elizabeth Rusch.

- An increasing argument by book banners is that the mere existence of a LGBTQ+ character makes that book “sexually explicit” and in violation of district policies. The result is the erasure of LGBTQ+ people from school shelves—and unfortunately, this trend is likely to escalate. This summer, in the Mahmoud v. Taylor case, the Supreme Court ruled that districts must provide “opt-outs” for children whose parents object to LBGTQ+ books. “Today the U.S. Supreme Court willfully discounted and ignored the expertise of trained professionals in the classroom,” noted NEA President Becky Pringle, about the Mahmoud verdict. “In the end, students are the ones who pay the price for censoring what books they can and cannot access and read.

In 2024-2025, the most banned author was horror king, Stephen King. Second was Ellen Hopkins, especially for her young-adult book “Crank,” which is loosely based on her oldest daughter’s real-life experiences as a teenager addicted to crystal meth. These bans not only impact authors’ financial health, but it affects their emotional wellbeing, too.

The book with the most bans? It was “A Clockwork Orange,” by British author Anthony Burgess. It’s a more than 60-year-old satiric novel, depicting a dystopian future full of violent young people and an extremist government.

Lately, PEN notes that bans are spreading to curriculum and materials. In Colorado, despite teachers’ recommendations, the Mesa County school board vetoed the use of the “Colorado Story” materials for fourth graders this year because it mentioned Black Lives Matters and negatively portrayed Christopher Columbus. In Florida, Collier County residents challenged a biology textbook because of mentions of climate change, evolution, and COVID-19.

The Opposition to Book Bans Is Growing, Too!

Even as book bans grow common, thanks to a few extremist politicians—and lately, the efforts of the federal government—most Americans oppose them.

Nearly 9 in 10 public school parents say they’re confident their local public schools are selecting appropriate books for their students to read, according to a recent Knight Foundation survey. Indeed, the people they trust the most to make decisions about reading material are teachers and librarians, Knight found.

By contrast, only 2 in 10 people think their state government or people who are not parents should be making those decisions, according to the Knight survey.

This opposition to book bans is fueling an energetic, dedicated effort to keep books in the hands of students.

- In St. Francis, Minnesota, educators prevailed. In June, the St. Francis school district agreed to return dozens of books to school shelves, settling the suit filed by the local union. “We achieved this settlement because parents, students, our community and even Minnesota authors stood with educators to defend the freedom to read in public schools,” said Education Minnesota-St. Francis President Ryan Fiereck. “The students’ stories and commitment to fixing this terrible policy were particularly inspiring.”

-

As of this summer, at the urging of union members, at least 11 states had passed “Freedom to Read” laws, including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington. "Libraries are more than warehouses where the grapes of knowledge are stored," said Delaware State Education Association President Stephanie Ingram, at the new Delaware law's signing in September. "They are safe spaces where we can grapple with the contradictions of our society, where we can explore both the roots of what divides us and build communities around our shared desire to understand ourselves and each other more.

Delaware Gov. Matt Meyer (seated) signed into law the state's "Freedom to Read" legislation on September 15 at Joseph E. Johnson Elementary school in Wilmington, Del. At far left is Delaware State Education Association President Stephanie Ingram. - In the DoDEA schools, the students’ lawsuit is pending. Meanwhile, a bill in Congress, introduced by Democratic Reps. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) and Chrissy Houlahan (D-PA) would reinstate the nearly 600 books and protect curricula from future federal censorship.

- Even in Florida, it’s possible to fight back! In August, a judge overturned parts of the state’s 2023 book ban law, saying they were unconstitutional and violated students’ First Amendment rights. He also said more than 20 books that have been banned in the state should be returned to shelves. They include: “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker; “The Kite Runner” by Khaled Hosseini; “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood; and “Looking for Alaska” by John Green. Green and author Julia Alvarez (of “How the García Girls Lost Their Accents,” which was also deemed “not obscene” by the judge) had sued the state and two Florida school districts.