Key Takeaways

- According to Pen America, there were more than 10,000 instances of books bans in the 2023-24 academic year—the highest number recorded yet.

- Calling them a ”hoax,” the U.S. Education Department under President Trump has rescinded all guidance on book bans.

- In March, Education Minnesota-St. Francis filed a lawsuit alleging the St. Francis school district was unlawfully banning books in libraries and classrooms “based on the ideas, characters and stories they contain.”

The first time a book was challenged in St. Francis, Minnesota, it was by a community member – not a parent, says Becky Vevle, a middle school language arts teacher in the district. The book, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews— which follows a teenage boy rekindling a childhood friendship with Rachel, who has leukemia—was examined by a review committee that Vevle serves on. They read the book, reviewed the rubric and decided to keep it in the library.

Then the school board changed the system last November – and based it off of a site called BookLooks. Founded by a member of Moms for Liberty, BookLooks.org rated books from one to five, with five referring to books with “aberrant content,” according to its site. Concerns that can contribute to a high score on Book Looks, which results in the book being removed, can be things like “racial commentary,” “controversial and social commentary,” and “alternate gender ideologies.”

“Books in my library that ... they would question were really popular with the kids, and that I had deemed appropriate for middle school kids. They wanted to use [Book Looks] as a resource,” Vevle says. “It was infuriating to me.”

If the rating was a three or higher, the school board would get rid of the book without consulting the review committee at all.

To Vevle’s knowledge, the new committee did not read the books or get community insight, only referencing the website when taking books off the library shelves. She says there were books in the national curriculum that could be taken away due to its Book Looks rating.

“How can we get them to change the policy back? Because Book Looks was just going to take everything away,” she says.

In March, on behalf of eight students, Education Minnesota-St. Francis, the local educators’ union, filed suit against St. Francis Area Schools for unlawfully banning books in libraries and classrooms. Book Looks ceased operations soon after.

The lawsuit alleges the policy violates Minnesota law and the state constitution – and claims the policy "is antithetical to the values of public education and encouraging discourse.” The same day, the ACLU of Minnesota filed a similar lawsuit on behalf of a separate group of parents.

Infringing on the Freedom to Read

Vevle has 2,000 books in her classroom, with around 1,700 unique titles available for her students. Many of these books are banned in school districts across the country.

“I think that people are afraid of things they don't understand,” Vevle says. “And they're afraid that kids are going to learn something that maybe they don’t want them to learn.”

The Minnesota state constitution protects the right of access to information, different ideas and viewpoints, according to the Education Minnesota lawsuit. The lawsuit also states that Minnesota statutes prohibit public libraries banning, removing, or restricting access to books based solely on their viewpoint or the message it conveys.

A lot of books that have been banned are popular in Vevle's classroom, including The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, which tells the story of a Black high school student from a low income neighborhood who goes to a suburban prep school only to witness her childhood friend get fatally shot by a police officer while he was unarmed.

Vevle says students like reading about people overcoming obstacles. Taking away these books takes away choices that could engage students, and it also limits their viewpoint, she adds.

“It's a disservice to the kids, to not learn about the world around them.”

Public schools are the ultimate equalizer for education, which is why it's important to protect these books, says Ryan Fiereck, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, as well as a parent, educator and the local union president.

“When we remove the books from our libraries what we're literally saying is there is a kid in another site or another location or another school district that gets more opportunity than you do,” he says. “And that's just unacceptable.”

Book Bans are Not a Hoax

In January 2025, a few days after Inauguration Day, the U.S. Department of Education dismissed 11 complaints related to book bans, describing these as false narratives and meant to advance the “book ban hoax."

The Education Department under President Trump has rescinded all guidance on book bans and will no longer employ a “book ban coordinator” to investigate book bans.

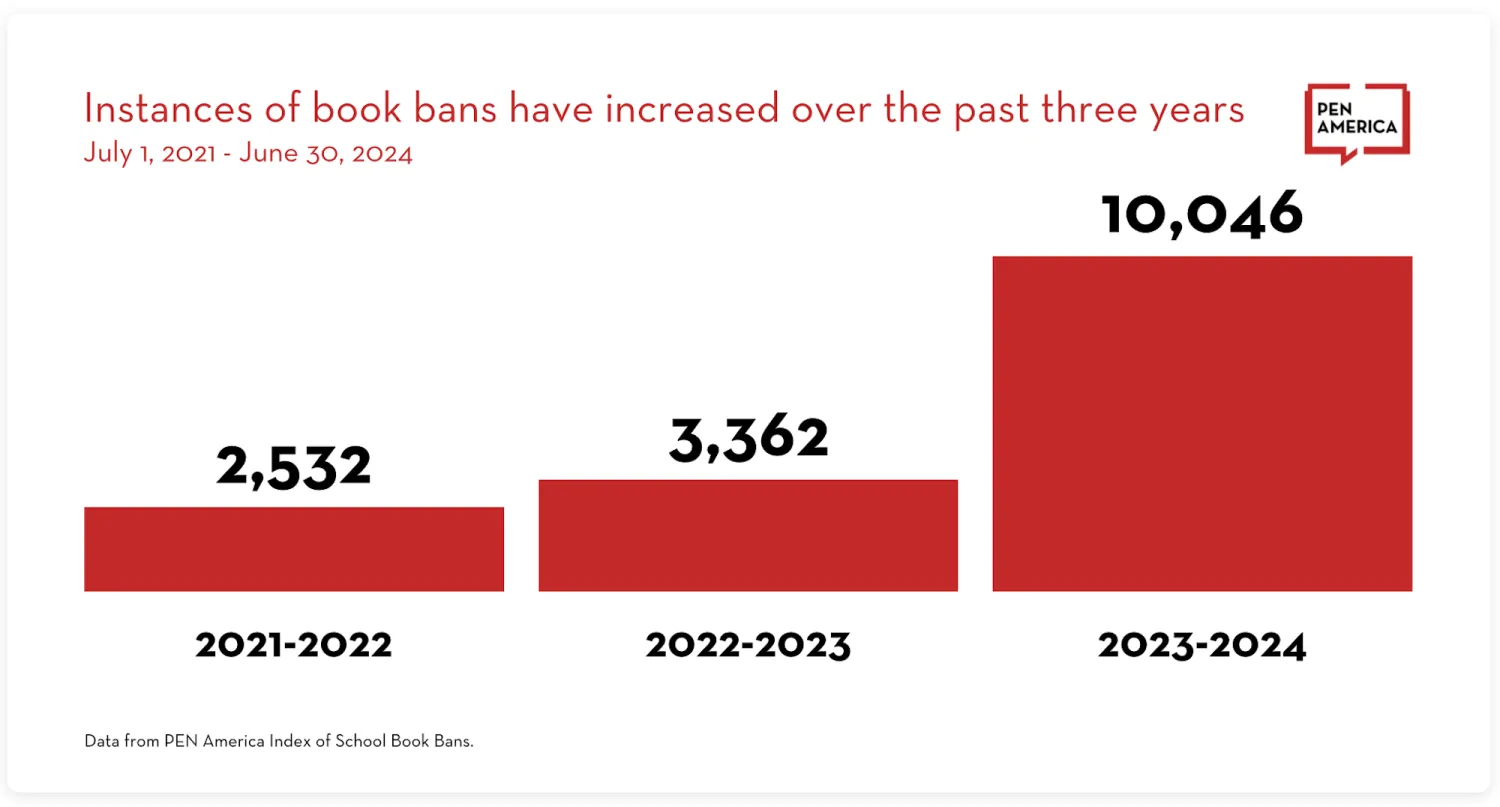

But according to a Pen America report released last November, there were more than 10,000 instances of books bans in the 2023-24 academic year.

“Anytime you take away access to a book based on ideological viewpoints, it's censorship and it's unconstitutional,” explains Tasslyn Magnusson, a senior advisor with the Freedom to Read program at PEN America. PEN America has been working to document the steep rise in book bans since 2021.

The targeted books, Magnusson says, usually relate to people with different sexual orientations, genders and races. Of banned books, 36 percent featured characters who were people or characters of color and 25 percent featured LGBTQ+ characters, according to a PEN America report.

These stories tell kids who they are and how to see the world.

“That’s one of the reasons why people want to take away books because they don't want them to think the world could include people who are gay,” Magnusson says. “Or include people who are Black or include people who come from a history where they were enslaved at one time.”

Magnusson has been working with community members to collect author statements and bring people together over the issue. Stories are ways people pass information to each other, ways people learn about themselves, she says.

“It's important to see storytelling as fundamental to who we are as human beings,” she says. “And so when we're attacking that, we're really attacking how we learn about what our identity is.”

Organizing in the Community

Nikki Kruse-Dye has two kids in elementary school in St. Francis who love to read.

“There’s going to be nothing left to read in our library at the rate that they're pulling books from our school shelves,” she says. “By the time my kids get into high school, there will be no important works of literature left in our library to inspire our kids.”

Kruse-Dye says she initially heard about the policy through other parents last November. She started seeing posts on the Education Minnesota Facebook page about it, prompting her to email her school board.

After seeing another Education Minnesota post about the banned books, she again emailed the school board. She was invited to speak at the next meeting.

“I initially declined, but I changed my mind,” she says. “So, I decided to post on Reddit and Bluesky to see if I could find other parents in the community who would come, just in solidarity.”

Although only seven others showed up to the meeting, Kruse-Dye searched social media for like-minded people. The group now has around 200 members, and they held a rally before a recent school board meeting. The students in school also organized a walkout before the meeting.

The district has since paused banning new books, but those already off the shelves have not been reinstated. Despite Book Looks shutting down, its ratings have been moved to the site Rated Books, Kruse-Dye says, which has a similar rating system.

She says she was surprised and encouraged by the amount of support from the community her group had.

“It's a predominantly red area, in terms of politics, and I thought I was all alone,” Kruse-Dye says. “And I am not alone. We're not alone, and now we know that.”