Key Takeaways

- Under intense pressure, teachers in every school district quickly acquired valuable new skills as schools shifted to remote learning.

- Decisions about how and what technology will be used in the classroom as school buildings reopen should be driven by educators, not for-profit interests.

- Digital technology can and should enhance and enrich instruction — with the right supports in place.

Maurice Telesford, a high school science teacher in Ferndale, Michigan, has always had a role for technology in his classroom. While Telesford, an engineer with a passion for STEM education, likely had less difficulty than others in adapting to full-time remote learning last spring, he wasn't spared the day-to-day frustrations. Teaching remotely for an extended and indeterminate period of time was in many ways “teaching with a blindfold on," he said.

The rapid transition to full-time remote learning when the pandemic hit was a shock to the system for all educators, students, and their parents. Even in classrooms where iPads, Google apps, and even smartphones were a constant presence, very few were prepared for teaching and learning to be completely dependent on access to technology.

And even for the tech-enthusiast educator, platforms like Zoom quickly lose their luster when they evolve from being an indispensable and engaging teaching tool into the lone, often impersonal and deeply flawed connection between educators, students, and their families.

The steep challenges and extreme pressure would have derailed a less dedicated group of professionals, said Telesford.

"The passion and lengths to which I've seen teachers and other educators working to help their students has reached an unprecedented level during this pandemic. The care of educators for students is unmatched."

It's a commitment supported by a high level of expertise, flexibility, and responsiveness.

“I feel like the system is generally thought of as stagnant and unable to adapt," said Telesford. “[This past year] has shown otherwise. The education system is capable of learning new skills in a short timespan.”

The End of the ‘Digital Dinosaur?’

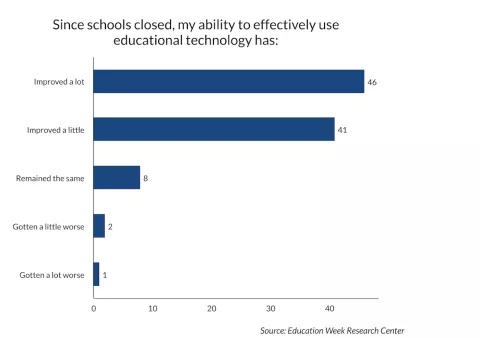

There's no question that many educators in every school district in the country acquired major new skills in digital technology that they didn't have prior to the school closings. Many were, and may still be, skeptical of technology's large presence in teaching and learning.

Before COVID, some teachers had already flipped their classrooms or were using Google classrooms, recalls Telesford. “But now everyone knows how to do it and that’s great.”

Any teacher who was a “digital dinosaur” before the pandemic isn't anymore, says Andy Hargreaves, a research professor at Boston College and co-president of the Atlantic Rim Collaboratory.

“I don't think there were really many teachers who weren't using technology in the classroom before the pandemic anyway. But anybody who was is now up to a baseline level of proficiency. We're at a new level, a new platform now.”

This is a welcome development — despite materializing in harrowing circumstances — but Hargreaves cautions educators and district leaders especially to keep their enthusiasm in check.

“We have to move forward, but believing technology - virtual instruction in particular — is the only path to innovation for schools as we come out of this pandemic is preposterous and dangerous,” said Hargreaves. “It is an area of innovation — but it's just one.”

A Narrative Resurfaces

According to the National Education Association's (NEA) policy statement on digital equity, amended in 2018, “The optimal learning environment should neither be totally technology free, nor should it be totally online and devoid of educator and peer interaction.”

Furthermore, educators, rather than “entities driven by for-profit motives,” should define the appropriate use of technology in education.

Long before the pandemic, it was these entities and their boosters in the media and legislatures who overhyped technology as the savior to the public education system. Failure to adapt and adopt quickly, we were warned, would weaken schools and cripple the nation's ability to compete in the 21st century.

This "Leap Before You Look" approach to adopting large-scale educational technology exacerbated the existing digital divide.

“People like to talk about opportunity all the time, but I always say without access, opportunity means nothing,” says Oklahoma drama and speech teacher Shawna Mott-Wright.

An NEA report released at the height of the pandemic found that an estimated one-quarter of all school-aged children live in households without broadband access or a web-enabled device such as a computer or tablet. (The American Rescue Plan, passed by the House of Representatives last week, includes $7 billion in emergency funding for the Federal Communications Commission’s E-Rate program to address the digital “homework gap”.)

“The pandemic’s speed forced school leaders to deploy whatever technology tools were readily available... But if this year of Zoom school and Khan Academy has taught educators anything, it’s that we should always think twice before trusting technology to do the yeoman’s work of educating the nation’s children.”

— Victoria E.M. Cain, Northeastern University in Phi Delta Kappan

Too often, however, districts would fast-track the purchase of expensive digital products. The level of enthusiasm seemed to increase with every new technological advancement — despite scant evidence that the resulting student outcomes justified the enormity of the investment and the upending of many classroom environments. Without teacher input from the outset, many schools ended up with high-priced products that didn't serve the classroom

Audrey Watters, author of the upcoming Teaching Machines, to be published by MIT Press in August, believes the value of Big Tech has been constantly oversold to schools and warns that the same hyperbolic claims are resurfacing as schools prepare for a post-COVID environment.

“This past year, technology wasn't the hero, educators were. But here we are again — seeing another attempt to push this narrative that teachers and schools cannot change,” Watters says. “This undermines the teaching profession and the students. But schools do innovate and they do change.”

Avoid the Hyperbole

The Rand Corporation recently released a survey of 375 school district and charter management organization (CMO) leaders to gauge their concerns for the 2020-21 school year. Three bubbled to the top: disparities in student learning during the pandemic, students' mounting mental health needs, and insufficient funding for school staff.

It was useful information and consistent with other surveys. But it was the report's headline that raised eyebrows and maybe some anxiety levels: “Remote Learning is Here to Stay.”

What prompted this conclusion was a response to a question about district plans for virtual learning. According to the Rand survey, two in 10 school districts and CMOs “have already adopted, plan to adopt, or are considering adopting virtual school as part of their district portfolio after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

David Garcia of Arizona State University calls the headline “misleading” since it is unclear how much of this result is driven by CMOs rather than school districts. In addition, one of Rand's recommendations — more funding support for remote learning — doesn't appear to align with the needs and concerns expressed by district leaders who participated in the survey.

While there's little doubt that remote learning in some form is a part of school districts' plans, “educators clearly have more pressing needs as they return to school,” said Garcia. “But a headline like that only gives those who are constantly championing technology, before and after the pandemic, more encouragement to push this narrative of ‘big tech is coming and there's nothing you can do about it.'‘”

It's more constructive to focus on how tech can “enhance face-to-face learning, not remote learning as the Rand report suggested,” Garcia adds. “There are things we can learn from this forced use of technology that can improve what we're doing in the classroom.”

So, What Is Here to Stay?

Despite the obvious deficits a year of remote learning highlighted — the decline in learning, the widening homework gap, the social isolation, the limitations of many digital tools — in many ways, there will be no going back, says Ann Coffman, manager of NEA Teacher Quality.

“I don't think it's realistic that educators return to exactly what they were doing prior to the pandemic and they probably shouldn't. There's a lot to be said for the skills that teachers have acquired over the past year. Some hybrid learning models can be effective — with the right supports in place.”

The integration of digital technology into instruction and practice will always require access to relevant, high-quality, interactive professional development for every educator. During the pandemic, NEA and its state affiliates built a network of members well-versed in using technology to support student learning. Through an ongoing series of webinars, these teacher-leaders have trained more than 20,000 educators.

Jaime Halbmaier-Stuart, an elementary school teacher in Maine and already fairly proficient in using technology, says she benefitted greatly from the NEA webinars and looks forward to continuing leveraging digital tools in her classroom. Before the pandemic, Halbmaier-Stuart was already using Google Classroom and other platforms well-suited to her 4th grade students.

“I'm lucky to teach in a forward-thinking district,” she says. “We've been trained but not on a lot of bells and whistles. We're not bombarded with the ‘very latest.’ I can tease out what works in the best interests of my students.”

Maurice Telesford believes schools should be given the space to innovate and that may or may not result in the adoption of more technology. Although he believes his students, like educators, have also learned valuable skills — independent learning, self-regulation especially — from the time spent learning remotely.

Ultimately, the conversation around the use of technology should continue to focus on one overriding concern, Telesford says. “Is it the best tool in that moment? Will it help solve the problem that’s in front of us? That’s what we have to always figure out.”

It's a conversation that should be expanded to include all educators, says Andy Hargreaves.

“A school should look at the positives but also the risks of new technologies that might be adopted. Let's get everyone in the same room — the teachers who are tech enthusiasts, those who are skeptics, but counselors and mental health specialists as well. That'll be a better conversation in helping every educator make a sound judgment on how to use this stuff.”