Key Takeaways

- Preparing for incidents of gun violence requires consideration of physical security, emergency operations plans, association protocols, development of media-related and other communications strategies, and the relationships that facilitate effective work on gun violence.

- Relentless and frightening school gun violence and media coverage of the incidents have created an earnest desire from school communities for protection, but some solutions are antithetical to fostering welcoming and inclusive school environments.

- Learn which solutions are preferred to ensure safe and welcoming school communities that have positive relationships with law enforcement and school staff who are well-prepared for emergencies.

School Gun Violence Preparation Executive Summary

The preparation section of the NEA School Gun Violence Prevention and Response Guide includes guidance on planning for gun-related scenarios and practicing, evaluating, and updating gun violence-related plans. It offers information on security upgrades to prevent shooters from accessing education settings like school buildings, classrooms, and campus facilities while also ensuring conditions remain welcoming and not prisonlike. This section also examines the efficacy and potential harm of active shooter drills and policing. For broader context and related recommendations, consult the other sections of this guide: Part One—Prevention, Part Three—Response, and Part Four—Recovery.

For state affiliate leaders and staff, and for local leaders, staff, and worksite leaders—like building representatives and faculty liaisons—the preparation section provides both association-focused and education- and community-related content, including advocacy opportunities and strategies. For example, an association should not be responsible for developing a school district, college, or university emergency operations plan, but association leaders, staff, and worksite leaders must know the details of those plans, where the association and its members fit in, how to improve plans, and ways to ensure appropriate association engagement when Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education respond to incidents of gun violence. For state and local associations, this section also includes information on how to develop protocols and relationships to facilitate responses to gun-related incidents.

Evidence-Based Security Measures

The following evidence-supported strategies help protect the safety of students and educators in education settings.

- Secure Entryways and Locks: Controlling access is the most effective physical security measure to keep shooters out of buildings. Strategies for preventing unauthorized access to education settings include installing security fencing, establishing single access points, and ensuring all exit-point doors are self-closing and lock upon closing.

- Examine School Policing: Partnerships among law enforcement groups, security personnel, and Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education can play vital roles in safety. The keys to these partnerships are training, clear roles, and accountability. If education settings do choose to have security personnel intervene in violent and dangerous situations, those personnel must be carefully selected and trained in trauma-informed practices and de-escalation techniques.

- Rethink Active Shooter Drills: Training for educators on how to respond to active shooter incidents is important; however, there is no compelling evidence that including students in such drills has any value in preventing shootings or protecting the school community. If a workplace insists on including students, they must adopt strategies to mitigate the harm of such drills.

- Understand and Engage with Emergency Operations Plans (EOPs): Developed by Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education, EOPs provide clear and uniform guidance and procedures for emergency planning and response. EOPs are important to the association because they include information on lockdown procedures, active shooter drills, and other policies of concern. In addition, implementing and practicing the processes in the EOP can save lives. Understanding the EOP process helps leaders and staff communicate with members about what the district and/or the school is doing to prepare and get a clearer sense of where their influence can make a difference and what roles the association can play.

Components of an EOP include a planning team; concept of operations (an overall plan); assigned responsibilities; control and coordination efforts; training and exercises; development and maintenance; legal basis for operations; and functional annexes, including lockdowns; evacuation; accounting for all students, educators, and visitors; communications; family reunification; public, medical, and mental health; and recovery.

Long-Term Media and Communications Strategy

To prepare for a gun violence incident, it is crucial to develop emergency tools in advance for swift deployment. Responsible parties should be ready to issue media statements, press releases, and internal messages to members, families, and other members of the community. The association should also have contingency plans for alternate systems of communication in case of cell tower outages or power failures and for those students and families without regular access to computers.

It is important for local and state association leaders to understand how and with whom they will interact after a gun incident. Identifying the right association leaders and the correct administration officials before an incident saves valuable time and can impact the safety of students and educators. It is also an opportunity for leaders to build relationships with relevant community organizations, including crisis response and racial and social justice organizations. There are often parent groups and other organizations concerned about gun violence that would welcome partnerships with educators.

Part 2: Preparation

Examining what physical security procedures, school policing measures, school environment considerations, emergency operations plans, and communication tools should be in place in case of a gun violence incident.

Find our comprehensive list of resources from NEA, Everytown for Gun Action, and other partners, including resources for developing emergency operations plans and assessing preparedness.

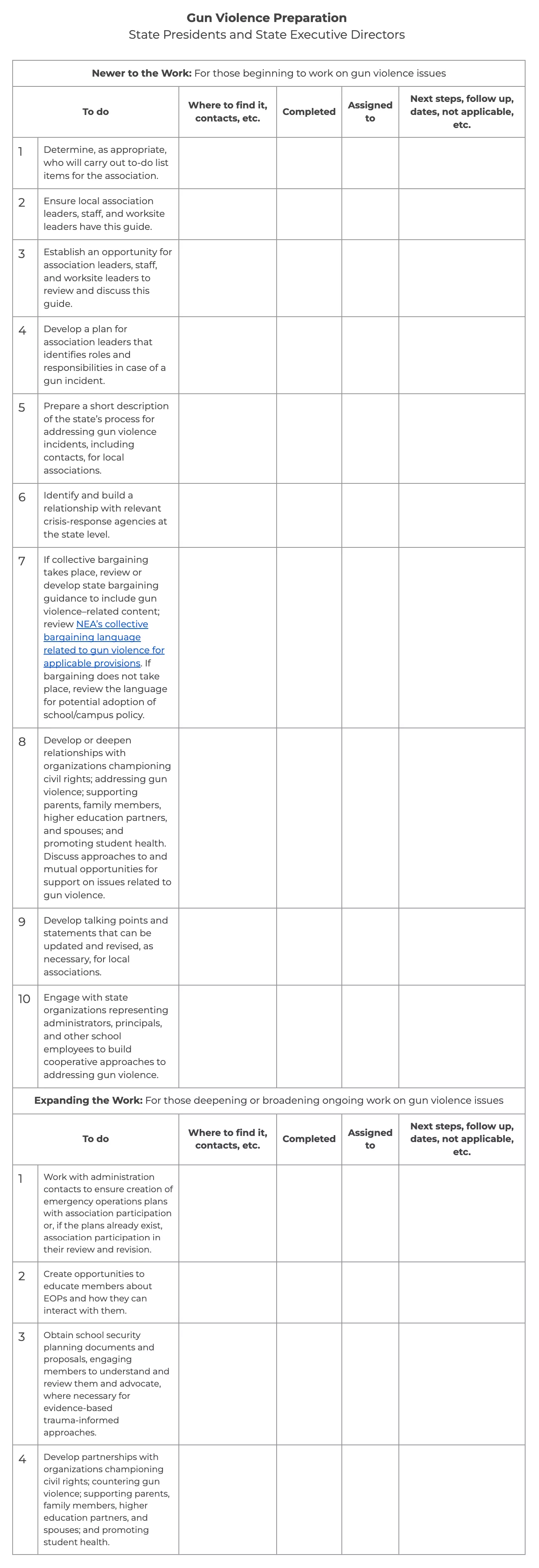

Effective preparation requires many factors and coordination within and between components of the association and with administrators and law enforcement agencies and partners. Download two checklists with strategies and action steps to help guide those beginning to work on gun violence issues and those who are further along in the process.

Preparing for Incidents of Gun Violence

Preparing for incidents of gun violence requires consideration of physical security, emergency operations plans, association protocols, development of media-related and other communications strategies, and the relationships and partnerships that facilitate effective work on gun violence. This component of the guide’s material on preparing for incidents of gun violence addresses each of these factors.

Employ Evidence-Based Approaches to Physical Security

Physical security is a critical intervention to keep guns out of education settings. Technology-based safety measures have evolved over the last decade and are increasingly common (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021); (Zhang, Musu-Gillette, & Oudekerk, 2016). Such measures include bulletproof windows, metal detectors, artificial intelligence for weapons detection, security cameras, and facial recognition technology. Security equipment can have a negative impact on students, and the effectiveness of some of these approaches has yet to be well-researched (Hankin, Hertz, & Simon, 2011); (Mayer & Leone, 1999).

NEA recognizes that school and college facilities and grounds should reflect welcoming, inclusive, and supportive environments for all students, parents, families, and communities and opposes the “[c]construction of prison-like school environments that employ metal detectors, random searches, and other building and design elements that diminish a thriving and nurturing school climate” (NEA, 2022). According to the American Psychological Association, implementing prison-like security measures in places like education settings and hospitals fosters a sense of threat, not safety. Additionally, these hardening measures, which are designed to prevent violence, often fail to address the most prevalent form of school-based violence and bullying (Hulac & et al., 2024). NEA recognizes the significance of physical school facilities as a reflection of what educators want our schools to be—welcoming, inclusive, and supportive environments for our students, parents/guardians, and communities.

For these and other reasons, NEA opposes prison-like school environments that employ metal detectors, random searches, and other building and design elements that diminish a thriving and nurturing school climate.

Here are examples of common school security measures:

- Entryways and Locks: Controlling access is a highly effective physical security measure to keep shooters out of buildings. Most experts, including members of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission and the Sandy Hook Advisory Commission, agree that the ability to control access must be a component of every school security plan (Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, 2019); (Sandy Hook Advisory Commission, 2015). Strategies for preventing unauthorized access to school buildings and campuses include installing security fencing, establishing single access points, and ensuring that all exit-point doors are self-closing and lock upon closing. State legislatures should provide funding for these basic access control measures. Internal door locks can serve as a secondary measure, allowing educators to lock doors from inside classrooms, buildings, and facilities. This protects students and provides law enforcement groups to time address threats. During mass shooting incidents at Sandy Hook Elementary School and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, lack of dual-locking or inside-locking classroom doors exposed educators and students to danger.

- Alarms/Alert Systems: Alarm and alert systems warn students and educators when there is an active shooter on school grounds or on a college campus. Such systems must be checked and updated regularly and the alert should differ from everyday announcements. The mass school shooting at Robb Elementary School in Texas brought such issues to light: The system’s use for non-gun-violence-related announcements diluted its effectiveness, and poor internet connectivity hampered its reach (Texas House of Representatives Investigative Committee on the Robb Elementary Shooting, 2022).

- Bulletproofing: Bulletproof glass can be effective but is very costly. Strategically placed tempered glass or ballistic film, which is a thin layer of polyurethane that can be applied to existing windows, may be a more economical way to slow down an intruder. This could allow more time for educators to activate safety protocols and for response teams to arrive (3M, 2024).

- Metal Detectors: NEA opposes the use of metal detectors in education settings. A research review of metal detector efficacy found mixed results, showing metal detectors could potentially reduce weapon carrying in schools (though this assessment did not specifically report on firearm carrying) but could also create a less trusting school environment. Visible security measures, such as metal detectors, also raise the possibility of ‘‘attack location drift,’’ which means motivated student shooters who are aware of metal detectors may alter their locations of attack to places like school buses, parking lots, or athletic events (Hankin, Hertz, & Simon, 2011); (Price & Khubchandani, 2019).

- Security Cameras and Facial Recognition: The effects of security cameras on behavior in schools have yet to be extensively studied. While some research has found that conspicuous security cameras in other types of settings may reduce unruly public behavior and increase pro-social or helping behavior (Borum & et al., 2010), it should be noted that perpetrators of school shootings may not care whether they are apprehended and thus may be undeterred by cameras (The Governor's Columbine Review Commission, 2001). A major concern about facial recognition software, in particular, is that it can be inaccurate and may disproportionately affect students of color, a problem exacerbated by the overreliance on intense surveillance measures in education settings that serve primarily students of color (Nance, 2017). Because facial recognition technology can be inaccurate, it can lead to students being punished for offenses they did not commit (Coyle & Curr III, 2018).

Examine School Policing

School resource officers and school security personnel should be properly trained to work with mental health professionals and other educators to apply trauma-informed practices, de-escalation measures, and crisis intervention practices. They should also receive implicit bias training, with the broad goal of fostering a safe, welcoming, and inclusive school community.

Policing in education settings must include continual reviews of discipline practices, data collection processes, and audits and transparency of budgetary allocation for school resource officers, private security, and other law enforcement in schools. Accountability measures for school resource officers and law enforcement engaging with children and students must be in place and reinforced.

NEA opposes the use of law enforcement personnel or private security in the discipline process and opposes hiring private security to perform the roles of school resource officers or sworn law enforcement officers. The Association believes that arming education employees as a preventative measure against armed intruders creates an unsafe environment, placing students and school personnel at greater risk. For additional information, see “Do Not Arm Teachers or Other Educators,” in Part 1 of this guide.

Relentless and frightening school gun violence and media coverage of the incidents have created an earnest desire from school communities for protection. However, the practice of policing in schools has not been shown to reduce school shooting deaths. One study examined 179 shootings on school grounds from 1999 to 2018 and found no evidence that school resource officers in schools reduced deaths or injuries from school shooting incidents (Livingston & et al., 2019). Similarly, another study found that while school resource officers reduced some forms of violence in schools, they did not prevent gun violence-related incidents and concurrently intensified suspensions, expulsions, police referrals, and arrests (Sorensen & et al., 2023). An analysis examining 133 school shootings from 1980 to 2019 found that having an armed officer at the school did not act as a deterrent for school shooters; instead, it suggested that an armed officer may serve as incentive, with their presence linked to increased casualties after a perpetrator’s use of assault rifles or submachine guns (Peterson & et al., 2021).

A national report using U.S. Department of Education data (2015–2016) found that having police in schools was associated with 3.5 times as many arrests compared to those schools without police. The report, which identified a disproportionate impact on students of color, found that funding decisions prioritized policing over student mental health in schools; it also identified more severe consequences in student criminalization and lower academic outcomes for students of color. Black students were three times more likely than White students to be arrested, and Indigenous students were twice as likely as White students to be arrested. Latino/a/x students were also more likely to be arrested than their White counterparts (Whitaker & et al., 2019). Research has also found that LGBTQ+ and gender-nonconforming students have a higher likelihood of being stopped by police, suspended, expelled, or arrested, and they often report feeling hostility from law enforcement groups in schools (Lambda Legal, 2015); (Himmelstein & Bruckner, 2011).

If created thoughtfully and carefully, partnerships among law enforcement groups, security personnel, and schools can play vital roles in school safety. Providing appropriate training, establishing clear roles, and strengthening accountability practices are key to the success of these partnerships.

In districts that choose or are required to have a security presence, the security professionals should have an exclusively protective role and be integrated within the school community, be answerable directly to school leaders, and receive training as peace officers, with an extensive focus on trauma-informed, de-escalation, and minimum-use-of-force techniques.

Rethink Active Shooter Drills

Plans, such as emergency operations plans (EOPs), that include active shooter drills must minimize harms from such drills. Although less than 1 percent of gun deaths per year occur on school grounds (Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, 2024-b), drills to prepare students and educators have become commonplace. However, there is no strong, conclusive evidence affirming the value of these drills for preventing school shootings or protecting the school community when shootings do occur. There is good reason to think they are ineffective, in part, because the preparedness procedures are being shared with the very individuals most likely to perpetrate a school shooting: former and current students.

NEA supports training for educators on how to respond to active shooter incidents; however, the Association does not recommend these drills for students. Educators should carefully consider the impacts before conducting live drills that involve students. Everytown partnered with Georgia Institute of Technology’s Social Dynamics and Wellbeing Lab to study the immediate and long-term impacts of active shooter drills on the health and well-being of students, educators, and parents. The research showed that students and educators experienced distress and, sometimes, lasting trauma as a result of active shooter drills (ElSherief, 2021). Putting a person in a scenario with the perceived threat of gun violence may activate a post-traumatic stress response, such as negative and distressing changes in thoughts, emotions, and behaviors for those who have a lived experience of gun violence.

If students must participate in active shooter drills, here are some helpful tips and resources to mitigate the harm that such drills can cause.

Before Facilitating an Active Shooter Drill

During an Active Shooter Drill

After facilitating an active shooter drill, all education settings should:

For more information, see the National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s comprehensive guide on how to create active shooter drills (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, n.d.). The American Academy of Pediatrics also frames concerns and considerations related to such drills (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2020).

Review and Practice Emergency Operations Plans

Emergency operations plans (EOPs) provide clear and uniform guidance and procedures for emergency planning and response. In the 2021–2022 school year, 96 percent of public K–12 schools had an active shooter plan (Burr, Kemp, & Wang, 2024). Ideally, the school team developing and revising an EOP collaborates with school and community stakeholders, including association leadership and members, other unions, parents and guardians, and, when age-appropriate, students.

A variety of models can be used to create EOPs, and state departments of education or other agencies as well as local jurisdictions are likely to have requirements and guidance of their own. The purpose of this NEA guide is not to have state or local associations create EOPs but instead to help association leaders, staff, and worksite leaders understand, assess, improve, and engage with them. It is important to help all stakeholders understand how EOPs can fit into their own planning for gun violence incidents.

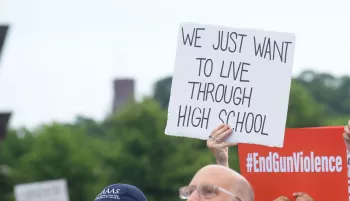

Given the variation in state and local EOP-related requirements and guidance, the NEA guide uses two models from the U.S. Department of Education: one for K–12 schools EOPs and one for institutions of higher education (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-a); (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-b).

A wide range of education stakeholders—and NEA members—have crucial insights, understanding, and perspective that will enhance the planning and assessment processes and outcomes. Districts and higher education institutions should provide language guidance and resources and communication-related support to integrate member input. For example, the U.S. Department of Education notes that continuity of services in the event of an emergency implicates essential functions like business services, communications, computer and systems support, facilities maintenance, safety and security, and continuity of teaching and learning (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-a); (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-b). These are positions often held by NEA members, who are well-placed to draw on their daily work to identify and assess hazards and needed responses.

EOP language on gun violence must also explicitly address the needs of disable students and educators with disabilities. Sixty-seven percent of students with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) spend more than 80 percent of their time in the general education classroom (National Center for Education Statistics, 2023). As a result, general educators must be aware of necessary IEP supports for students with disabilities in case of emergencies, including incidents of gun violence. Educators who have worked with students with disabilities can assist with understanding the breadth of necessary EOP responses, including for people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); individuals with non-apparent disabilities; students and educators with autism; and students and educators who are hearing impaired, have low vision, or have developmental or mobility disabilities or other conditions that may warrant an individualized response.

The Importance of School Emergency Operations Plans to the Association

Implementing and practicing the processes detailed in an EOP can save lives. These plans provide guidance on:

- A range of possible hazards and emergencies;

- Lockdown procedures, active shooter drills, and other policies of concern; and

- The roles and responsibilities of school administrators during an emergency, which provides transparency and a clearer sense of how the association may fit in.

By understanding the content and processes included in EOPs, association leaders and staff can more effectively communicate with members about what the district and/or school is doing to prepare for a gun violence incident. Leaders and staff can also rely on that understanding to develop and implement plans for engaging with administrators on EOPs, including members in EOP processes and committees, and educating members about effective responses to gun violence incidents.

The EOP Process

In both K–12 and higher education contexts, the U.S. Department of Education approaches EOPs with a six-step process, recommending each step be carried out by the planning team. The department noted, “The common thread found in successful operations is that participating organizations have understood and accepted their roles” (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-a); (U.S. Department of Education, et al., 2013-b).

In reviewing the key components of EOPs, consider how the following association-related questions may apply to each component:

- What association leadership and member expertise could be helpful on the team or committee?

- Who do you know on an existing team or committee who can help expand participation to include association leaders and members?

- What relationships and partnerships do you have that could bring community voices into the process?

- How well do EOPs reflect the diverse and intersectional perspectives and experiences of Native People and People of Color, LGBTQ+, and from all economic backgrounds and abilities?

- How might association advocacy improve these EOP components?

- What formal role do association leaders and members play in this process?

- What other documents, including collective bargaining agreements and school board policies, exist with content relevant to EOPs?

- How might the association address EOP-related concerns through collective bargaining and administrative policy?

- What existing association and labor-management committees exist that do or can take on EOP-related issues that address gun violence, including health and safety committees, violence committees, and school health committees?

Components of an EOP

Planning Team: The team should consist of representatives from across the Pre-K–12 school or higher education institution.

Concept of Operations: This refers to the overall plan of how the school will protect students, faculty, and visitors in the event of a gun violence incident. Examples include who has the right to activate the plan. This section of an EOP may also address how association leaders are notified when the EOP is activated.

Assignments of Responsibility: Each plan should include an overview of broad roles and responsibilities of school administrators, association members, families and guardians, community organizations, and first responders. These responsibilities should be articulated clearly, and association leadership should ensure that members are notified and involved in defining their roles.

Control and Coordination Efforts: This is the relationship between the school or district EOP and the broader community’s emergency management system, with consideration for who has control of the equipment, resources, and supplies needed to support the school.

Training and Exercises: The plan should include training objectives, frequency, and types of preparation drills related to a gun violence incident. The association should check relevant collective bargaining or policy language about when and how frequently such training and exercises will be held.

Development and Maintenance: The plan should include the process for developing and revising the plan.

Legal Basis for Operations: This refers to the legal basis for emergency operations and activities.

Functional Annexes: Functional annexes refer to several specific operational areas, including lockdowns; evacuations; shelter-in-place; accounting for all individuals; communications; family reunification; public, medical, and mental health; security; and recovery. The following components are essential to the emotional and physical well-being of members, students, and families:

- Lockdown: This refers to securing school buildings and grounds during incidents that pose an immediate threat of gun violence to ensure that all educators, students, and visitors are secured in rooms away from immediate danger.

- Evacuation: This refers to vacating school buildings and grounds following an incident of gun violence. This section of the EOP should include how to evacuate people with disabilities and others with access and functional needs, such as language and medical needs. In addition, the planned location to reassemble students and educators should be addressed. In higher education institutions with multiple buildings, it is important to identify multiple areas of evacuation.

- Sheltering in Place: This takes place when students, employees, and visitors are required to remain indoors for an extended period due to a threat of gun violence.

- Accounting for All Students, Educators, and Visitors: This must take place to determine the whereabouts and well-being of students, staff, and visitors and to identify those who may be missing. This should include developing a plan to determine who is in attendance in the evacuation area and what to do when a student, educator, or visitor cannot be located.

- Communications: This guide includes recommendations for communicating with students, educators, families, and the broader community before, during, and after a gun violence incident.

- Family Reunification: It may be necessary for students, educators, and visitors to reconnect with families to ensure that every student is released to an authorized adult and that students in Pre-K–12 schools do not leave on their own. College-age students can be released on their own; however, emotional support for every individual who has experienced the trauma of a gun violence incident is important.

- Public, Medical, and Mental Health: This refers to the actions taken to address emergency medical and mental health issues in coordination with appropriate emergency medical health services and other relevant groups. An example of what is included in this section of the EOP is how the school will secure enough mental health counselors to support the needs of students and educators.

- Security and Capacity: This includes actions taken by on a routine, ongoing basis to secure the school from threats originating both inside and outside the school, ensuring that the school is physically secure.

- Recovery: This refers to how to recover in the aftermath of a gun violence incident. The recovery section of this guide covers this topic in-depth.

Develop Tools for Communicating Information Via Digital and Media Platforms

To prepare for a gun violence incident, it is helpful to develop emergency communication tools in advance to facilitate swift deployment. Actions include the following:

- Develop and be prepared to deploy develop an emergency association-related homepage, connecting it to the district homepage if possible or connecting the district page to the association’s;

- Explore with administrators the potential to establish a joint information center that includes the association;

- Create templates for posts for X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, and other social media platforms to provide regular updates, as appropriate;

- Prepare press release and statement templates;

- Maintain an email list of stakeholders, including educators, media, and elected officials;

- Establish alternate systems of communication in case cell towers are inoperable or electricity is out and for those students and families experiencing homelessness or without regular access to computers;

- Identify translation services, if appropriate;

- Develop electronic message templates to provide the latest information;

- Draft letters or emails to educators who work at the site of the incident, to those in neighboring institutions, and to parents;

- Develop frequently asked questions and answers that can be distributed to the media and posted on the crisis website;

- Ensure that communications contacts in the state affiliate and local associations are up-to-date and easily identifiable; and

- Identify state and local affiliates who can assist with communication and other resources and support.

Build Strong Partnerships

Addressing gun violence in education settings requires strong, meaningful relationships with partners to deepen association understanding, build relationships, strengthen the processes and policies of Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education, and ensure that approaches developed to keep students, educators, and communities safe are culturally and racially appropriate.

From state to state and within states, potential partners may vary. An important place to start is with other unions representing workers in the Pre-K–12 schools and institutions of higher education where association members work, gun violence-focused organizations, racial and social justice organizations, after-school programs, mental and physical health providers and organizations, associations representing principals or other administrators, and local colleges and universities with programs that identify or address violence in communities or, more specifically, in education settings.

The following list includes several national-level organizations—with links to their websites—that may have state or local counterparts. Identifying local groups working on similar topics may also serve the same purpose.

- AAPI Victory Alliance

https://aapivictoryalliance.com/gunviolenceprevention - AASA—The School Superintendents Association

https://www.aasa.org/resources/all-resources?Keywords=safety&RowsPerPage=20 - Alliance to Reclaim our Schools

https://reclaimourschools.org - American Academy of Pediatrics

https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/gun-violence-prevention - American Psychological Association

https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/gun-violence-prevention - American School Counselor Association

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Prevention-of-School-Rela - Color of Change

https://colorofchange.org - Community Justice Action Fund

https://www.cjactionfund.org - Hope and Heal Fund

https://hopeandhealfund.org/who-we-are - League of United Latin American Citizens

https://lulac.org/advocacy/resolutions/2013/resolution_on_gun_violence_prevention/index.html - Life Camp

https://www.peaceisalifestyle.com - Live Free

https://livefreeusa.org - March for Our Lives

https://marchforourlives.org/ - MomsRising

https://www.momsrising.org/blog/topics/gun-safety - NAACP

https://naacp.org - National Association of Elementary School Principals

https://www.naesp.org - National Association of School Nurses

https://www.nasn.org/blogs/nasn-inc/2023/07/27/take-action-to-address-gun-violence - National Association of School Psychologists

https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-safety-and-crisis - National Association of Secondary School Principals

https://www.nassp.org/community/principal-recovery-network - National Association of Social Workers

https://www.socialworkers.org/ - National PTA

https://www.pta.org/home/advocacy/federal-legislation/Public-Policy-Priorities/gun-safety-and-violence-prevention - National School Boards Association

https://www.nsba4safeschools.org/home - Parents Together

https://parents-together.org/the-heart-of-gun-safety-and-a-new-approach-to-advocacy - Sandy Hook Promise

https://www.sandyhookpromise.org - The Trevor Project

https://www.thetrevorproject.org - UnidosUS

https://unidosus.org/publications/latinos-and-gun-violence-prevention